09-17-2011, 06:59 PM

09-17-2011, 06:59 PM

|

#12 (permalink)

|

|

Gen II Prianista

Join Date: Jul 2009

Location: Ballamer, Merlin

Posts: 453

Thanks: 201

Thanked 146 Times in 89 Posts

|

FWIW, I'm the one who posted an answer at CleanMPG.

Here's what I said, I only wish that it were shorter:  In a simplistic way, what your friend said is correct about aircraft.

In a simplistic way, what your friend said is correct about aircraft.

But I don't see it being applicable to road vehicles. Here's why:

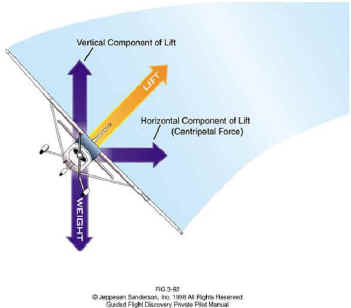

In sustained level, constant velocity flight an aircraft's lift is the same as the aircraft's

weight. In a banked turn, what was the lift vector in level flight now has two

components; a vertical component, and a horizontal one called centripetal force.

In order to keep flying level in the turn, the pilot needs to increase the

vertical component

to equal the planes weight. One way to do this is to increase forward velocity which

increases lift and the vertical component. If the bank angle of the turn is increased,

more velocity/power is required to keep the vertical forces balanced and the plane in

level flight.

What your friend was probably trying to convey was the idea that where a long

straight run-up to increase velocity is not available, an aircraft flying in a circular

pattern and increasing the bank angle and increasing the forward velocity to provide

the necessary lift can achieve a similarly high velocity.

(While it is not strictly needed in this primer, as bank angle is increased, to make a

"coordinated turn," some rudder and elevator inputs are also needed.)

The problem with a car is that there is no lift vector to generate centripetal force.

Things get a little sticky here. Some folks would have us believe that in a turn there

is a thing named centrifugal force pulling the car and occupant outward. As I

understand it, the correct interpretation is that the turning wheels generate a inward

centripetal force but the momentum of the car and its occupant is in a straight line.

The car and the occupant appear to be pulled outward as the vehicle undergoes a

constant acceleration -- change in velocity or direction -- in the turn. But it is only the

difference between their tendency to want to continue in a straight line, and the car's

turning inward.

For a car, the inward centripetal force needed to successfully negotiate a turn can only

come from the friction of the contact of the tires with the road. This is a constantly

changing function of the:

* stickiness of the tires -- they get sticker as they heat up,

* suspension -- amount of compression, shock rebound/dampening rates,

* front/rear weight distribution -- it changes under acceleration and braking,

* individual tire loading -- for vertical load analysis purposes a four wheeled vehicle is

"indeterminate," which is to say very difficult to calculate with certainty,

* turn radius -- constant, increasing, decreasing,

* angles of departure between the line of travel and each tire's centerline,

* road surface -- texture, dry/wet, sand/gravel, flat/wavy

and probably some other stuff as well.

For any given degree of road surface banking on a roughly circular course that has a

constrained usable width -- a road, an off ramp -- there is only so fast you can go

before the tires start to loose traction and loose some or all the formerly generated

centripetal force that was holding the car in the turn. Sure, you can add more steering

angle when the front tires begin to scrub, or you can add power to get the powered

wheels spinning.

But these things would require using more fuel in the turn, not less.

And then, I could be wrong... again.

Last edited by Rokeby; 09-17-2011 at 07:06 PM..

|

|

|

|