Lots of advertisements will tout “real world” fuel economy increases and testing procedures in an attempt to make their product look more desirable. Surely, if you wanted to buy something to increase fuel economy, testing that proves it actually does would be good, right? And what’s more conclusive than someone actually taking the thing you plan on buying and driving around with it?

Well, unfortunately, it’s not that simple.

How the EPA does testing

The EPA doesn’t just stick a driver in a car, give them a course, and tell them to drive around it and hope that they do it consistently every time. Instead, they put test vehicles up on a dyno and run a course designed to simulate driving.

Many people fault the EPA for this method, but I believe they have put a lot of effort into developing and refining their testing methods, and at the very least, they are internally consistent, which is what’s most important when comparing vehicles. In fact, it is internal consistency that the EPA is most concerned with, and also the reason that their EPA ratings often conflict with our own real life observations.

Sure, the EPA may have rated my car at 27 mpg combined, and I might get 40 mpg by EcoDriving it, while you might be upset that you only get 25 mpg by driving normally. But therein lies the great flaw of “real world” fuel economy numbers. No driver, road, traffic, or weather condition is ever consistent enough to make comparison fruitful.

How scammers do testing

Using acetone as an example of a scam (and not wanting to link any pages for fear increasing their reputation with Google), you can see that it’s proponents will often talk about “beating the EPA” or the “inefficiency of modern internal combustion engines.” They use these buzzwords to lead you into their story, which hinges on “real world” benefits for “drivers like you.”

Acetone rests on a very shaky, some would say fraudulent, technical background, and relies mostly on “evidence” from fuel economy “tests.” Most of these tests, however, consist of walking up to someone who has never thought much about fuel economy and telling them, “Hey, I’m going to put this stuff in your tank and you’ll see 30% better fuel economy.” From there, the testers, who sometimes don’t even calculate fuel economy, will give reports like, “I’ve driven my car with acetone for two weeks now and the needle is still above the halfway line! OMGLOLWUT.”

Other, slightly more intelligent scammers will run tank-to-tank testing, meticulously recording their findings, but ignoring major variations in weather, type of driving, or driving technique. Just take a look at my fill-up history from the last three years and tell me if you think it’s a consistent enough to base tests on:

Other, even trickier scammers, usually companies, will pay for “3rd party” testing to be done at some “university” or other credible place. This is a tricky area, because there are many reputable places working on fuel economy testing, but there are also many devices that’ve “shown increases” at such facilities that have also been declared scams when brought to court by the government or investors.

How I do testing

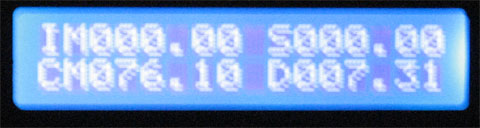

I use my MPGuino to record fuel economy over predetermined courses using predetermined driving techniques. I try to be meticulous about what RPM a shift at, how much throttle pressure I use, and control as many factors as I can. However, I’m not here to say that even given how much effort I put into it, I’m not much better than those scammers.

Recently, I attempted to test fuel economy changes when removing the alternator belt on my car. It’s relatively well-known that the parasitic drag from the alternator reduces fuel economy. However, I was interested in seeing for myself the difference that it made on my own car.

In NJ, where I usually reside, I have a test loop where I can usually get mpg reading within +/- .5% through consistent driving. Generally, others have high confidence in these tests due to the low deviation in my results. In MO, where I am now, there is a similar loop, albeit a hilly one. I used the same ideas to test my fuel economy with the alternator, without the alternator, and then with the alternator again, and these were my results:

First, I’d like you to notice that the distance was a very consistent 7.31 miles. Now, please notice how inconsistent the mileage readings were. I lost mpgs without the alternator, then lost them again when I reattached it! These numbers are, of course, not good, and a result of faulty testing. Not only are they not internally consistent, but they are inconsistent with the results that many others have demonstrated.

So who should you believe?

The takeaway here is that you can’t take fuel economy testing at face value. Not from me, or anyone else. The people most worth trusting are those that are transparent about the difficulties of accurate numbers and their testing methods. Take a look at the methods used and decide for yourself if they are prone to error or not. And remember, even the most well-intentioned testers can make errors.

If you liked this post, sign up for out RSS Feed for automatic updates.

Popularity: 2% [?]

{ 2 comments }

On your alternator test, there are some variables which may have influenced your outcome. I can give you an explanation for your results which may explain them. This is of course only a logical guess which would need a follow up test with consistent voltage. Tell me if I got anything wrong here.

On your lower than expected 2nd result from taking off the belt:

First, if your voltage was not kept around 14V then your fuel pump may not have been up to stock pressure, reducing the vaporization of fuel and thus FE.

Second, the spark may have been a lower voltage and temperature reducing the efficiency of the combustion from stock.

On the last result, when you reattached the belt, the alternator began charging the now partially discharged battery making the parasitic load higher than the first result where, I’m assuming, the battery was fully charged.

Sound reasonable?

I realize, of course that even if my analysis of your experiment is correct your point is still valid that “real world” fuel economy numbers must be taken as error filled data, not hard evidence.

Comments on this entry are closed.